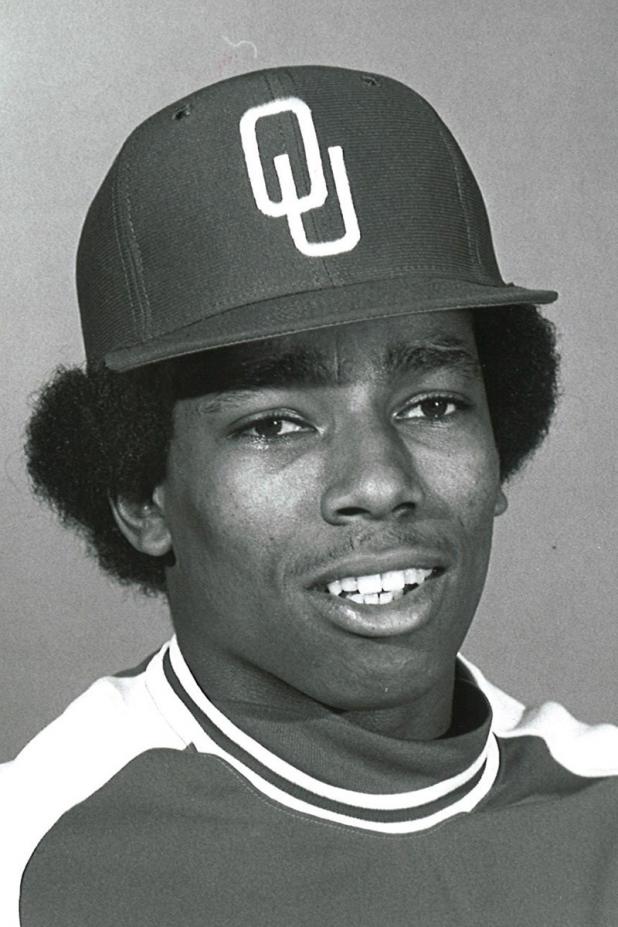

Sooners honor Olney's Michael Pace for Black History Month

The University of Oklahoma baseball team played its first game in 1898. The Sooners first claimed a National Championship in 1951 and again in 1994. In program history, over 1,000 different players have earned a varsity letter for OU on the baseball diamond.

Forty years ago at the Sooners’ old Haskell Park, abutting the southwest corner of Owen Field, Michael Pace quietly became a small but significant part of the long and storied tradition of OU baseball. In the spring of 1977, Pace became the first African-American baseball player to step into the batter’s box as a Sooner.

Major League Baseball had been integrated 30 years earlier with Jackie Robinson playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Black male athletes began to take up an increasingly significant role in the structure of collegiate football and basketball rosters, but in the mid-1970s baseball was still behind.

Opportunities to play baseball had been few and far between for Pace; growing up in Olney, Texas, with a population south of 4,000.

“I didn’t play baseball in high school because we didn’t have baseball in high school,” recalled Pace. “It was Olney, Texas, and the name of the school was Olney High School. I ran track and played basketball, played football, but only played baseball in the summer. Maybe, 10 to 15 games a summer. Just American Legion type stuff. I didn’t want to play any other sport than baseball. I had letters in school from track, football and basketball, but I wanted to play baseball so I walked on at Texas Tech.”

In the fall of 1973, Pace arrived at the Lubbock campus and was granted an opportunity to try out as a walk-on. After making the team in fall tryouts, he appeared in one game as a freshman in the spring of 1974. Starting as the designated hitter against No. 1 Texas, Pace would play in his first and only game for Texas Tech.

Following fall ball in 1974, Pace was notified by the coach that there was no longer a use for him or a spot on the team. The time had come for him to cut his ties with the program and try to land somewhere else; somewhere that would give him a fair chance to showcase his talents on the diamond.

“I shouldn’t have had any trouble making the team at Texas Tech, but it just happened to be one of those things where no other black folks could even come try out. I had to have a football player talk to the coach just to get me a chance to try out at Texas Tech.”

As a 20-year old college athlete, this was not the first time that Pace’s journey needed to get around a road block. From first through fifth grade, he could not attend school in his hometown, because the public school system had yet to be integrated in Olney. For 43 miles each direction, Pace and roughly 20 other kids in Olney were bussed north to Wichita Falls.

“Starting in the sixth grade was when Olney integrated. That was 1965 or ’66 when I started going to school there. Pretty much in high school, I was the only black guy on the football team, basketball team, track team, you name it. It didn’t just start at Oklahoma, it was pretty much all my life. I kind of embraced that. I knew people wouldn’t let me play. So when I got the opportunity, shoot, I tried to embarrass everybody out there. That was one of the logs on the fire that kept me going.”

Looking to keep his competitive fire lit, it was Oklahoma that appeared on Pace’s radar as a potential landing spot after speaking with a friend who attended OU at the time. Pace’s first priority was to try and find a school that competed at as high a level as his last school in order to challenge himself as a baseball player.

Pace had tracked down the phone number to OU head coach Enos Semore and arranged a meeting on campus. He and his parents, Alfred and Arstine, made the drive to Oklahoma and on the word of coach Semore that he could get a tryout the decision was made that Pace would attend OU in the fall of 1975.

“It was one of the best choices that I could have made.”

Pace would make the Sooner roster in the fall and sit out the 1976 spring season as a redshirt. The following year, he made the team again and earned a spot on Oklahoma’s traveling squad.

“I did a lot of running around with guys by the name of Mickey Lashley and Keith Drumright,” said Pace. “Those were my two guys that kind of took me under their wing because I didn’t know a soul there. I spent a lot of time with those guys on the field and off the field. Mickey said, as far as he knew he hadn’t played with any and it was his last year there. Out of all the teams that we played that year, I saw one black guy played for the University of Colorado and then Arizona State had two and I think USC had one, which was Anthony Davis. KT Landreaux and Bobby Pate were the guys for Arizona State. I’m not sure what the name of the guy for Colorado was. There just weren’t a whole bunch of black folks playing baseball at that time.”

Pace was not alone in 1977. The Sooners added freshman Joe Oliver to the roster that season. An outfielder from Fort Worth, Texas, Oliver would soon become the second black baseball player in Oklahoma history.

“Joe was a freshman and I was a fourth-year junior. He walked on and suited out at the home games, but he didn’t go on the road, which means that he didn’t letter that year. I remember, Joe and I would go out when the game was pretty much all sewed up. We got to go out and play a position for the last one or two innings. I remember him going out one time in left field and I was in center.”

Despite the lack of diversity found in college baseball, Pace was able to successfully traverse the season through all of the ups and downs, experienced by all baseball players regardless of race. The opportunities were few-and-far-between on a stacked Oklahoma team that was coming off its fifth-consecutive trip to the College World Series in Omaha and it would take a second chance for Pace to get his shot at making an impact on the Sooners’ season.

“I started seven games at Oklahoma,” recalled Pace. “All of them were DH, except for one. One of the first games was in Hawai’i. I faced a guy by the name of Derek Tatsuno.”

The Sooners weren’t the only team to fall victim to Tatsuno, the Hawai’i ace, who would become college baseball’s first 20-game winner and in 2007 was inducted into the College Baseball Hall of Fame.

“He just mowed us down. I was 0-for-3, three Ks and I didn’t get to play anymore. I said, ‘Shoot, there goes my chance.’ As time went on, I got to start against Oral Roberts in a doubleheader as the designated hitter. Then I was the designated hitter at Oklahoma State in a doubleheader there and a doubleheader against the Salukis up in Illinois.”

Box Score

Box score from Pace’s first game for the Sooners against New Mexico in 1977 (click to enlarge).

Pace’s first official appearance for the Sooners came against New Mexico on March 15, 1977, at home. He went 2-for-3 with a pair of runs in a 14-4 OU victory. His 0-for-3 against Hawai’i came three days later and buried him on the bench for nearly a month.

In the biggest of series, Pace had his number called by Coach Semore to face Oklahoma State on the road on April 15. He hit ninth as the designated hitter and came through in a big way. Oklahoma pounded the Cowboys, 19-6, and Pace contributed a 2-for-3, two-run, two-walk, two-RBI performance with a double in game one of a doubleheader from University Park in Stillwater.

In the nightcap, Pace remained in the nine-hole as the DH and was integral in a narrow 3-2 victory to sweep the doubleheader. He went 1-for-2 with a walk and a go-ahead home run in the top of the fifth inning.

“When we went to play up at Oklahoma State, there were quite a few things being yelled out at me, while I was out there,” Pace remembered. “That isn’t the first time that that’s happened. It happened in high school quite a bit. Anyway, I’m batting on the road, I swung at a pitch and missed it and somebody stood up and yelled, ‘Hey, that ain’t no watermelon you’re swinging at up there!’ I acted like I didn’t even hear it, backed out of the box and got back in and then I hit a home run one or two pitches later.

“In another game, I was sliding into third base and I could hear the n-word. They were calling me that while I was on third base. Stuff like that doesn’t bother me. Shoot, that just let me know that they saw me out there. When you play Oklahoma State, they’ll say anything to get you off your game.”

The Cowboys would come back to tie the game, 2-2, in the bottom half before OU took the lead for good on a home run by Art Toal. Pace’s feat had been crucial to a Sooner victory, but had become overshadowed and there was no mention of it in the following morning’s Daily Oklahoman.

In limited action, Pace was able to put together impressive offensive numbers. He hit .349 (15-for-43) with 11 runs scored. He owned a .429 on-base percentage and .721 slugging percentage on four doubles and four home runs with nine RBI. It was enough to attract the eye of several major league scouts.

“I had no idea that I would get drafted. Shoot, I didn’t play very much at all. I was playing up in Wichita, Kansas with Gene Stephenson, who used to be an assistant coach at Oklahoma. He always let me play during the summer. I went up that summer and had gone up the summer before because I just wasn’t getting to play. When you don’t play, you can’t get better without playing in real games. I was playing for a summer ball team called Country Time. During the June draft, he came down to my room. We were all getting ready to play a game and he had told me I got drafted. I was an 11th round draft pick with the Philadelphia Phillies in ’77.”

Pace signed with the Phillies and spent three seasons in their farm system. He totaled 239 games played and 208 hits with 147 runs scored, including a career-best 111 hits, 83 runs and 21 doubles at Single-A Spartanburg in 1978.

Upon leaving professional baseball, Pace worked for Sysco Foodservice as an account executive. He and his wife Amanda had a daughter Lauren and he would finish his degree in 1988 with a bachelor’s of science from the University of Houston. Pace retired in 2013 and now resides in Atlanta, Georgia.

At his home, Pace dedicates a room to his baseball career and the career of some of the game’s greatest black players to come before him. Surrounding a picture of himself finishing a home run trot in an Oklahoma uniform are the images of baseball legends Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell and several others; who had fewer opportunities, but paved the way for Pace to have his.

Nearly four decades after having last suited up for the Sooners, he returned to Oklahoma in October 2016 for the team’s alumni weekend. The final event of the weekend was an alumni game at L. Dale Mitchell Park, the home of Sooner baseball that opened five years after Pace left OU. He got the opportunity to pull on his old number three, lace up and swing the bat in the crimson and cream one more time.

“It was one of the best choices that I could have made,” Pace said of attending Oklahoma.

“I really didn’t feel any tensions of me being on the field. All of the guys just seemed to accept me. There were never any wisecracks or anything. It was just all business. We worked hard every day, trying to get better. We worked super hard. Our goal was to win a championship and that’s what we did.”