U.S. veteran with ties to Olney awaiting kidney transplant

U.S. Marine Corps veteran Scott Gardner recalls gathering at “The Barn” at the Kelly place on Hutchins Road in Olney for the Hog Hoot in the ‘90s. People from all over the country crowded into The Pipeliner Inn and Olney homes for the Labor Day weekend bash, starting with a barbecue dinner that first night.

Mr. Gardner, 57, wants to make more memories like the Hog Hoot – but he needs a new kidney to do it.

Mr. Gardner, who lives in Red Oak and works as the gen- eral manager of an automotive shop, suffers from polycystic kidney disease passed from his grandmother to his mother, his brother Troy - a fellow Marine - and himself.

Polycystic kidney disease is a hereditary ailment in which clusters of cysts grow in the kidney, enlarge them, and may stop them from working. Mr. Gardner had the disease under control until 2022 when a bout with Guillain-Barré syndrome accelerated the deterioration of his kidneys.

“I was paralyzed completely for two months and came back from that. That’s when [doctors] noticed that my kidneys [function] had gone down,” he said. “That made my situation worse.”

Last April, doctors at Baylor Scott & White Health in Dallas put Mr. Gardner on the national transplant list, telling him that it would take approx- imately five years before he received a kidney from a deceased organ donor. That organ would be placed in his body beside his failing kidneys to help them function, he said.

In the meantime, he began searching for a living donor whose gift of a kidney would allow doctors to remove the two diseased organs, now fluid-filled and weighing a cumulative 30 pounds, he said.

“I’m not trying to be picky but I want these two contaminated kidneys out of my body,” he said. “Between work and treatment, I have about an hour and a half every day to spend with family.”

The hunt has not yet yielded a match; family members with polycystic kidney disease are not candidates nor are people taking prescription medication of any kind, he said.

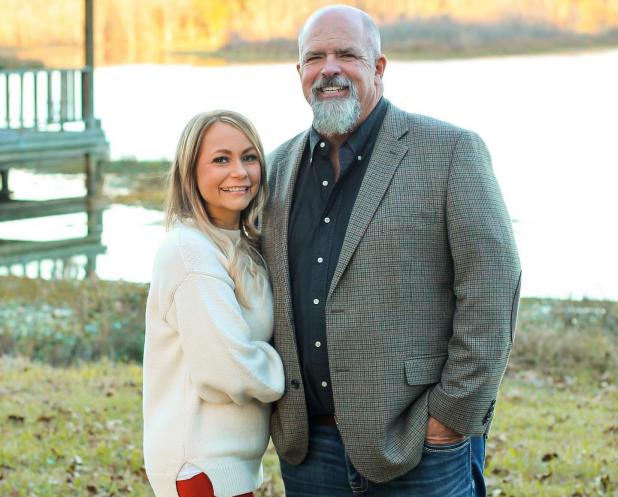

Mr. Gardner has adapted to his situation – still working full time and spending 10 hours each night hooked up to a dialysis machine at his home, he said. His wife, Monique is a nurse manager at Baylor Scott & White and helps with his nightly treatments.

Monique's first hus band died in an accident and she decided to donate his organs. Now, she and her two children face the prospect of losing the man who stepped in to become a husband and a father to them - for want of an organ donor.

Mr. Gardner said his health insurance will pay for all costs of matching him with a donor.

“This is a very hard ask but my family and I are very hopeful that I will find a living donor, this would mean that I could get transplanted sooner and would be such a blessing,” he said in a Facebook post.

For more information, go to LivingDonorDallas.

org or call 214-820-GIFT (4438) and refer to Scott Gardner, birthdate June 28, 1967.

Potential donors may also reach Mr. Gardner and get more information on donor options via his Facebook page.