Community moves to protect Black heritage

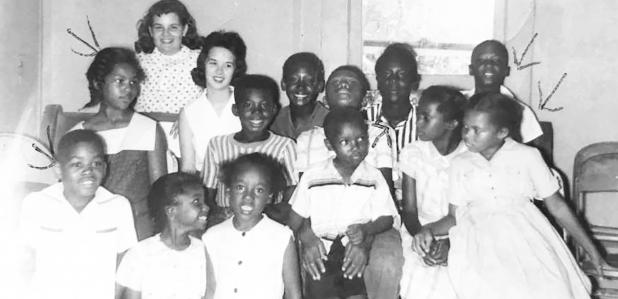

As the Olney City Council considers a request to allow members of Olney’s African-American community to purchase two foreclosed lots on the site of the Black church and school on the east side of town, a review of the Olney Enterprise archives shows the challenges Black families faced in getting access to education.

One of the first mentions of the one-room building that served as both a church and school at 411 East Elm Street, long demolished, appeared in the Enterprise in 1939. The story, entitled “Teacher for Negro School Elected,” reports on “a new teacher at the negro school.”

“Miss Jo Letha Runnels of Mineral Wells was elected on a one-year contract as a teacher for the negro school by the Board of Education Thursday night,” it said in the July 21, 1939. Ms. Runnels was a graduate of the Normal School at Prairie View and held a degree in home economics. She was contracted to teach all the children, regardless of grade level.

The newspaper archives do not show when Ms. Runnels left Olney, but the school was shuttered three years later. The Enterprise reported in 1947 that “Olney’s negro school, inoperative since the 1942-43 school year, will reopen next fall.”

“Reopening the negro school, if a teacher could be secured, was authorized for Superintendent J. D. Fulton by the School Board at its recent meeting. This week the superintendent had located a teacher. She is Laura I. Vaughn of Prairie View A&M College, and at present is secretary to the registrar there,” the newspaper said A year later, the Enterprise reported that the school had to close again, apparently because no substitute could be found for the ailing teacher.

“The Negro school did not open this week due to the illness of the teacher, Ola Blanchette. She has been ill in a Fort Worth hospital. With an expected enrollment of 4 students, the Negro school will Open Monday 13,” according to a Sept. 9, 1948 article.

By 1959, African-American parents asked the Olney School Board to let their children attend all-Black schools in Wichita Falls. The Enterprise reported on May 7,1959: “The board also decided to investigate costs of transferring all pupils in the Negro school here to the Wichita Falls schools. This was at the request of local Negro patrons.”

The Enterprise reported in 1962 that it “cost the Olney Independent School District a total of $2,988 to send 29 Negro students to school in Wichita Falls last year.”

“(Because of the lack of adequate Negro school facilities in Olney and the segregated status of the local white schools, Olney has sent its Negro students to schools in Wichita Falls for the last several years, transporting them to and from their classrooms in a school bus daily.)” the newspaper said.

On May 30, 1964, the Enterprise reported: “Parents of Negro children in the Olney Independent School District have told the local school board they prefer to continue sending the boys and girls to school in Wichita Falls next year, rather than integrate with the Olney schools. Negro parents had been sent letters inviting them to meet with Olney School Board Tuesday night to discuss possible integration next year. ... The board had let it be known to the Negro families that any Negro students who applied for admission to the Olney public school would be admitted.”

Michael and Brenda Pace were among about nine Black students to attend Olney schools when they were finally integrated in 1966.